Making Sense of the Koch Network

Connect with the author

In recent years, two multibillionaire brothers, David and Charles Koch, have become major players on the political right, inspiring journalists and public interest researchers to comb through publicly recorded donations to depict a vast Koch network – as, for example, in the widely distributed “Maze of Money” chart created by OpenSecrets for the 2012 election cycle. In the current legal environment donations are often secret, so this approach necessarily misses money flows. Ironically, it also includes too many groups, ranging from longstanding conservative giants that get modest Koch donations to short-term fronts set up to write checks for attack ads.

An Evolving Political Strategy

Using information from SourceWatch and journalists, my research group on “The Shifting U.S. Political Terrain” focuses on enduring organizations created and directly controlled by the Kochs and their closest associates. Donations are not the key, because the Kochs have always collected resources from other donors, as they now do on a huge scale at twice-a-year “Koch Seminars.”

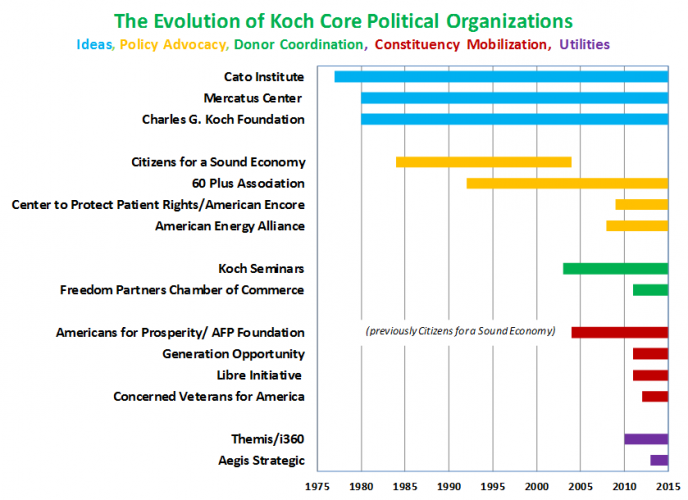

The chart in this brief arrays core Koch political organizations chronologically and functionally. Groups could be added and classifications debated, but the chart features the most important organizations and offers a coherent picture of the evolution of an overarching political strategy.

- The earliest and most enduring organizations – especially the Cato Foundation, the Mercatus Center housed at George Mason University, and the Charles G. Koch Foundation – aim to shape political ideas and world views. Taking ultra-free-market ideas seriously, the Kochs fund libertarian intellectuals and mount seminars for donors, operatives, and young people.

- From the 1980s and 1990s, Koch advocacy organizations engaged major policy battles about energy and climate regulations, taxes, and government’s role in social security and health care.

- From the mid-2000s, the Koch network turned to mobilizing activists and contacting voters for elections and policy battles. The key move was building a centrally directed nationwide federation, Americans for Prosperity – which had paid directors and staff in 15 states by 2007, and expanded by 2015 to 34 states encompassing 80% of the U.S. population. Themis/i360 was launched to collect and analyze real-time voter data; and specialized organizations manage outreach to key constituencies such as young people and military veterans. The most important of these is the Libre Initiative, working to attract Hispanic support in electoral swing states.

By now, the Koch network parallels, rivals, and leverages the Republican Party itself, both nationally and in most states. The aim is not merely to elect or appoint conservative Republicans, but also to prod them into carrying through an overarching agenda – to hobble the U.S. public sector by slashing taxes, removing regulations, and eliminating or privatizing social spending on health, education, and social security.