The White Supremacist Origins and Modern-Day Practices of U.S. Mass Incarceration

Connect with the author

Beginning in the 1970s and 1980s, a confluence of policies and practices produced the phenomenon we now call mass incarceration. Prison populations, especially state prison systems, grew exponentially—not because crime rates were rising, but more so because certain behaviors were criminalized and social institutions were dismantled. Programs and services for those struggling with poverty, substance abuse, and mental health issues saw their budgets decline; millions of federal dollars that had once provided income support, affordable housing, and treatment for mental health and substance use were re-directed toward law enforcement and state prison systems.

Not only does the United States incarcerate a higher percentage of its population than any other nation on the planet, but the racial disparities in our carceral system are profound: Black men are six times more likely to be incarcerated than their white counterparts. An understanding of the reasons for this disparity is critical for policy actors who want to reform the current system.

A Brief History of Race in U.S. Law and Law Enforcement

It is a uniquely American narrative that white supremacy, which is codified into law, provides the foundation for our major institutions, including the criminal legal system. In 1662, just a few years after the first people who had been kidnapped from the western shores of African arrived in the colony of Virginia, the Virginia House of Commons set forth two key conditions of slavery as it would exist in the United States: the establishment of people of African descent as less than fully human (which was re-codified in 1787’s 3/5ths compromise that determined how slave-holding states’ populations would be represented in Congress, and again in the 1857 Dred Scot decision where the Supreme Court held that even formerly enslaved people were property and not citizens) and the legal creation of the categories of “white” and “slave” so that a child’s race was determined by mothers’ and not fathers’ racial identity.

It is well documented by U.S. historians such as Talitha LeFlouria and David Oshinsky that the roots of law enforcement in the United States began with the slave patrol. Locally established (and typically formalized by the government) slave patrols operated across the South, capturing the enslaved who dared risk their lives for freedom. Our work highlights data that reveal how these white supremacist origins are not only the foundation of, but equally currently integral to, modern-day U.S. law enforcement practices. On every single measure, as the data demonstrate, Black people are disproportionately targeted and surveilled by law enforcement, resulting in significantly higher rates of incarceration.

How the Over-Surveillance of Black Bodies Fuels Incarceration Rates

Black people are over-surveilled in every space in the criminal legal system; they are more likely to be the targets of “stop and frisk” policies and traffic stops, to be convicted of crimes, to serve longer sentences, to be sent to solitary confinement, to be wrongfully convicted and often to be exonerated only after having spent decades in prison. They are also more likely to be killed by the police, even when and especially if they are unarmed.

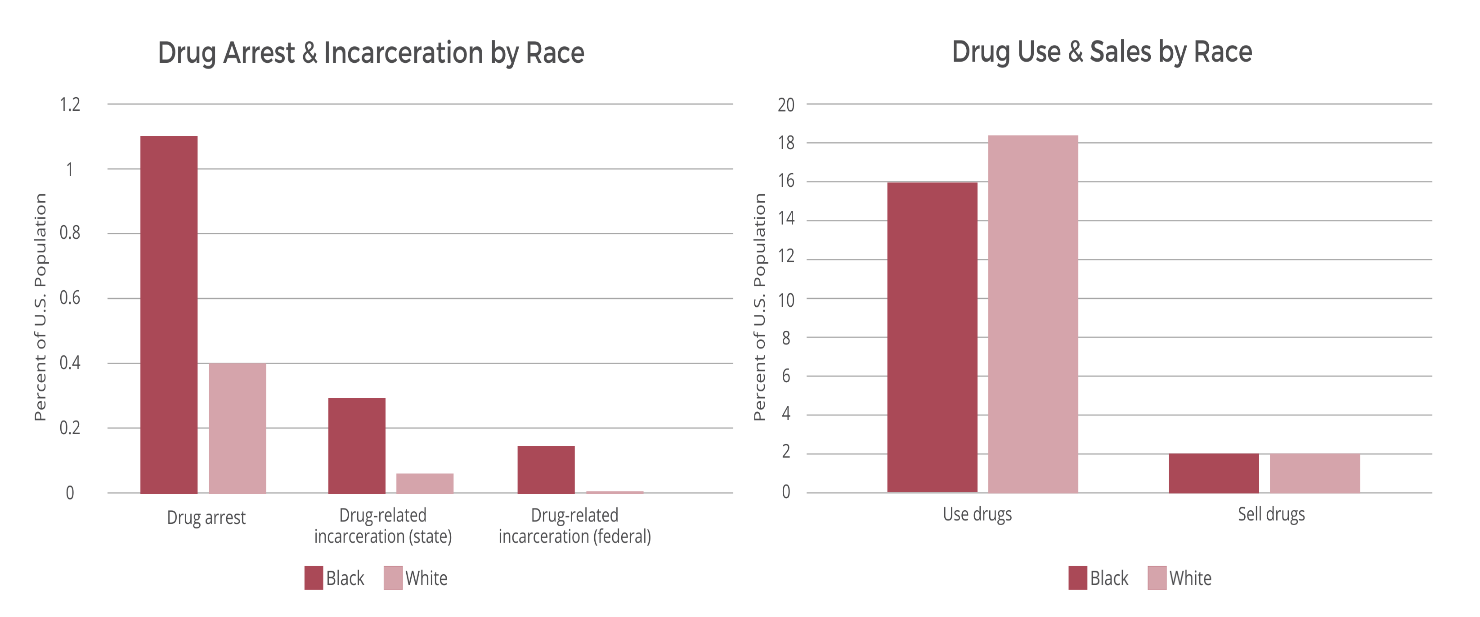

Stop and Frisk: Though some version of the practice of temporarily detaining people to question and search them for evidence of criminalized behavior has been present in various communities throughout U.S. history, “stop and frisk” was a particularly significant law enforcement practice in New York City between 2003 and 2013; at its height, more than 100,000 people were stopped and frisked annually. Research by the political scientist Andrew Gelman and colleagues revealed that Black and Hispanic individuals were more likely to be stopped and frisked than white subjects, even when controlling for precinct-specific variables and race-specific estimates of crime involvement. Simply put, theoretically race-neutral law enforcement policies were implemented in racist ways; Black and Hispanic people were disproportionately “stopped and frisked” even when controlling for the likelihood that they were engaged in criminal behavior. This finding is consistent with data on drug use, surveillance, and criminal legal involvement.

The War on Drugs: It is the subject of much-informed speculation that the War on Drugs—the U.S. federal government-led, global initiative to curb the international illegal drug trade launched by then-President Nixon, expanded by then-President Reagan, and deeply embedded in the criminal legal system by then-President Bill Clinton—was a thinly veiled war on Black people existing as citizens in the United States. This view is corroborated by a 2016 interview with Nixon’s former domestic policy advisor John Ehrlichman, as we recount in our 2021 book Policing Black Bodies: How Black Lives are Surveilled and How to Work for Change. Sentencing disparities between people found in possession of two different forms of cocaine (“crack”—disproportionately found among the Black population, versus powder cocaine—disproportionately found among whites) are an essential component of the War on Drug’s constellation of domestic policies. And, despite minor adjustments to these racialized laws by the Obama and Biden administrations, crack cocaine use continues to be more heavily sanctioned in ways that contribute to the disproportionate incarceration rates of Black people. These policies play an undeniably significant role in the overall racial disparities of mass incarceration: Of the 2.3 million people who are incarcerated in a variety of institutions, nearly 50% are Black men, even while Black people are no more likely to use drugs than their white counterparts.

Sociologist Erik Olin Wright argues that these policies comprise something much more insidious than simply a “war” on Black people; mass incarceration, he argued, was a tool to remove Black people from the social-political economy in an era when slavery and genocide were no longer tolerable in a modern democracy. Accepting what history and current data say about the innately and demonstrably white supremacist project of mass incarceration is a prerequisite for policy change that can bring about actual justice.

Read more in Eddie Glaude, Jr., Begin Again: James Baldwin’s America and Its Urgent Lessons for Our Own (Penguin, 2020); Angela Hattery and Earl Smith, Way Down in the Hole: Race, Intimacy, and the Reproduction of Racial Ideologies in Solitary Confinement (Rutgers University Press, 2022); Talitha LeFlouria, Chained in Silence: Black Women and Convict Labor in the New South (University of North Carolina Press, 2016); David Oshinsky, Worse than Slavery: Parchman Farm and the Ordeal of Jim Crow Justice (Free Press, 1997); and Erik Olin Wright, Class Counts: Comparative Studies in Class Analysis (Cambridge University Press, 1997).