Connect with the author

Research has long shown how expansion of supportive services can be used to prevent crime and support the formerly incarcerated. In 2020, the push to shift funds away from the criminal justice system and toward social services moved from activist spaces into the national conversation, as protestors demonstrating against racism and police brutality poured out into the streets following the highly polarizing murder of George Floyd. In the years since, policymakers have had to grapple with how different constituent groups perceive the threat of crime and the role of social services, while following what rigorously sourced evidence says about how to keep crime rates trending downward and while responsibly managing state budgets. One government-administered benefit that appears to have an effect on how well those convicted of a crime are able to reenter society and avoid further infractions is the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP), still popularly known as food stamps.

In a recent study, we find that accessible food stamps programs can serve as a crime control measure, preventing recidivism among those with prior convictions. We studied the impact that the drug felony ban on SNAP had on recidivism in California. This ban was passed as a part of the Personal Responsibility and Work Opportunity Act of 1996 (PRWORA), and banned anyone convicted of a drug felony from receiving SNAP for the rest of their lives. Our findings show how these restrictions appeared to fuel further criminal offenses and increased costs for the state.

State Variations in SNAP Administration and Drug Felony Bans Affect Recidivism

The drug felony ban on SNAP is a federal policy, but states can modify or repeal the ban altogether. To date, 21 states still have the ban in place with modified conditions, all of which create higher barriers to access and limit the number of people who receive SNAP benefits. For instance, Kansas requires that those with drug felony convictions complete an approved drug treatment program and pass a drug testing plan; if a person receives a second drug felony, they are banned from accessing SNAP for life. In Minnesota, applicants with drug felony convictions must pass random drugs tests, and are banned for life if they fail two. Missouri also makes drug testing a requirement, and applicants must pay for it themselves. One state, South Carolina, still has the full ban: A single drug felony conviction means that after that South Carolinian has served their sentence, they can never receive SNAP funds to help purchase groceries.

Even in states with modified bans, the barriers to access can be so high that they keep people from applying for and receiving SNAP even when doing so is technically possible. How can a SNAP applicant be expected to pay for expensive drug testing when they do not have enough money to buy food? Participation in an approved treatment program can be difficult as well, as programs often have long wait times before they can accept new patients.

In addition to the bans, SNAP programs can be administered in varying ways, leading them to be more or less accessible. Even though SNAP is a federal program with standardized income eligibility and benefit levels, local policies and practices such as outreach, work requirements, services offered, sanction rates, and other agency norms can affect a recipient’s experiences.

When it can be accessed, SNAP is widely utilized by people after incarceration to help support their reentry. A study in Boston found that 74% of people re-entering society received benefits. This period after incarceration—when people are trying to find housing, obtain employment, and address health and relationship issues—can be a very challenging time. Approximately 62% of people released from prison are re-arrested within three years. Rather than helping those re-entering society get back on their feet, the drug felony SNAP bans create conditions that are ripe for recidivism, creating a scenario in which people cycle in and out of the criminal justice system rather than rebuilding their lives. This comes at a tremendous cost to both those being denied SNAP and to taxpayers: In California, for example, it costs an average of $106,000/year to incarcerate one individual, while a single person’s SNAP benefits for the year total up to $3,372 at most. If broad access to SNAP benefits can help decrease recidivism rates, giving more people access to food stamps could save money in the long-term.

Data from California Illustrate SNAP Bans’ Effects on Arrests

California modified the ban in 2004 and opted out entirely in 2015. But we were able to study the impact of the ban by examining data from before and after it was first enacted. We conducted a comparison study between two groups: those who were banned from receiving food stamps and those who were not. In California, the ban barred people from receiving SNAP benefits if they were convicted of a drug felony after August 22, 1996. We analyzed the re-arrest rates of the unbanned group (defined as those with convictions in the three months before August 22, 1996) and rates of the banned group (defined as those with convictions in the three months after).

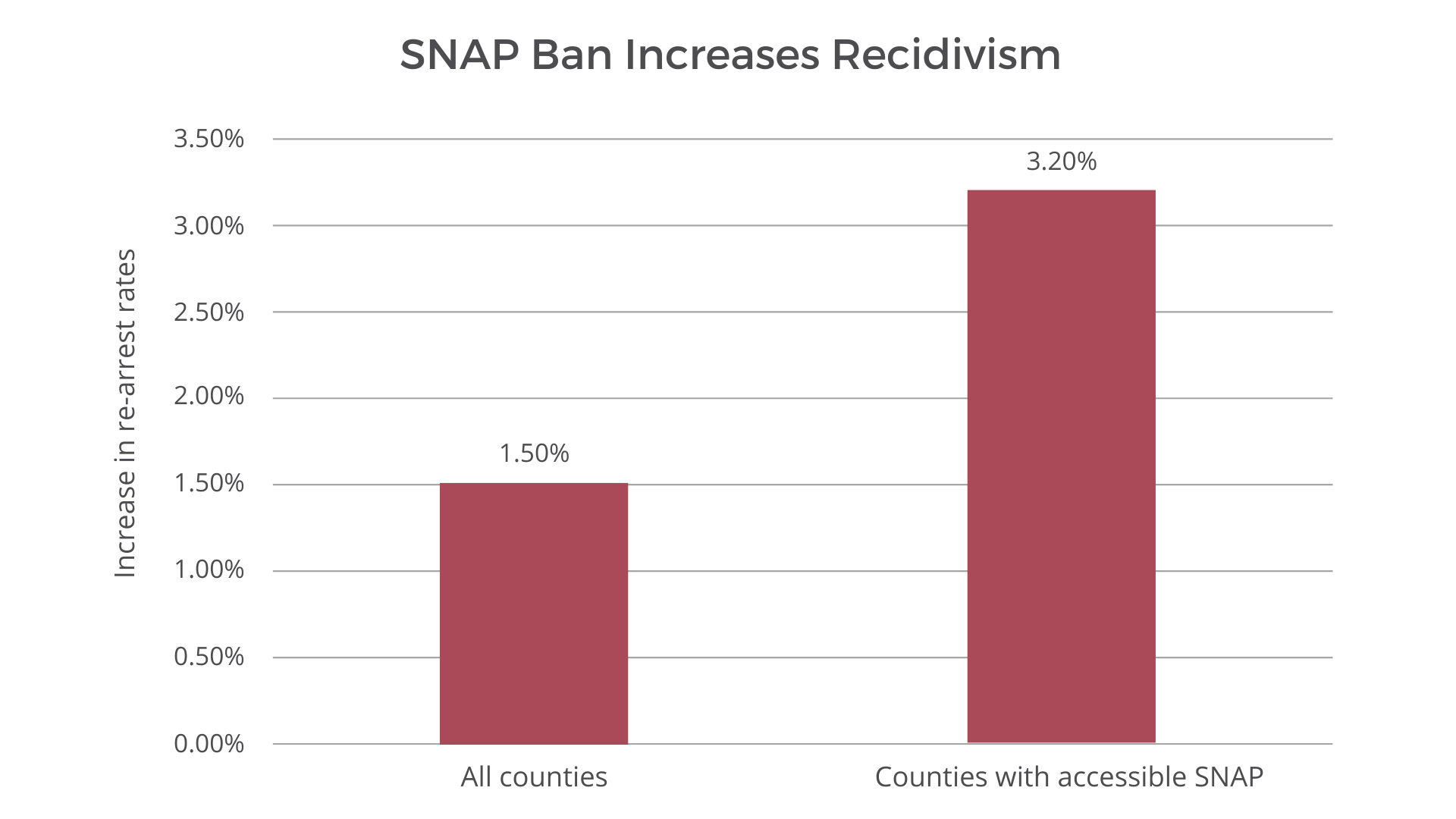

We found that those banned from receiving SNAP were not only more likely to be re-arrested, but they were also re-arrested faster than those who were not banned. We found that at any given point in time, the ban increased a person’s risk of arrest by 4%; cumulatively, over a 5-year period, being banned from food stamps results in a 1.5% increase in arrest rates. We also considered the accessibility of SNAP benefits in each county: In counties with more barriers to accessing SNAP, there was no notable difference in recidivism before and after implementation of the ban; conversely, in counties with more inclusive SNAP access, there was a 9% increase in the risk of being arrested at any given point in time. Cumulatively, over a 5-year period, being banned from food stamps in these more accessible counties results in a 3.2% increase in arrest rates.

Policy Implications beyond California

Given our research findings, it is clear that less restrictive SNAP programs are beneficial to people’s success in reentry and can be one piece of an effective crime control approach. Policymakers can:

- Repeal the federal ban in all states, including the 21 states with modified bans. States like Kansas, Missouri, and Minnesota may have modified the ban, but they continue to create high barriers to receiving SNAP. South Carolina could repeal its ban in order to increase access to SNAP and reduce recidivism.

- Ensure that food stamp programs are accessible to all eligible individuals. Policies and practices can deter people from accessing food stamps, even if they are eligible. Reducing administrative barriers to applying for benefits (e.g., not requiring fingerprints, drug tests), lengthening periods between recertifications, providing benefits in easy-to-use methods, and not requiring work reporting have all been shown to increase access.

With ongoing debates about public safety and the most effective allocation of taxpayer dollars, our findings support policy changes that broaden access to food stamps as one form of crime control. Inclusive welfare policies not only reduce poverty, but they also help reduce crime and recidivism.

Read more in Naomi F. Sugie and Carol Newark, “Welfare Drug Bans and Criminal Legal Cycling.” American Journal of Sociology (July 2023).