How Do State Licensing Boards Handle Applicants with Criminal Records?

Connect with the author

State licensing boards are responsible for determining whether applicants meet the requirements to practice a licensed profession. Now that roughly 25% of U.S. jobs require a state-issued license, understanding the structure of state licensing systems is very important. Applicants with a criminal record face significant challenges in obtaining a license. The issue is important to policymakers who are interested in their state’s policies’ impact on employment rates and on recidivism. While many states have moved away from the most ambiguous licensing restrictions (which likely deters many applicants with a criminal record from even applying), more can be done to ensure the process that regulates entry to professions is administered safely and equitably.

Because the likelihood of having a criminal record is not uniform across the population, excluding applicants with a criminal record is likely to have a disparate impact across various sub-populations. For example, women will be less affected than men. African Americans and Latinos will be more affected than European Americans, who will be more affected than East Asian/Pacific Islanders. These problems are compounded when licensing restrictions are framed in ambiguous and expansive terms, such as limiting entry to those of “good moral character.” Open-ended exclusionary standards make it difficult for applicants with a criminal record to determine whether they will be able to obtain a license, and are an invitation to unprincipled and discriminatory decision-making. What regulatory frameworks are operating across different states, and how do they encourage or deter applicants with criminal records?

Variations in State Licensing Guidelines and Bases for Exclusion

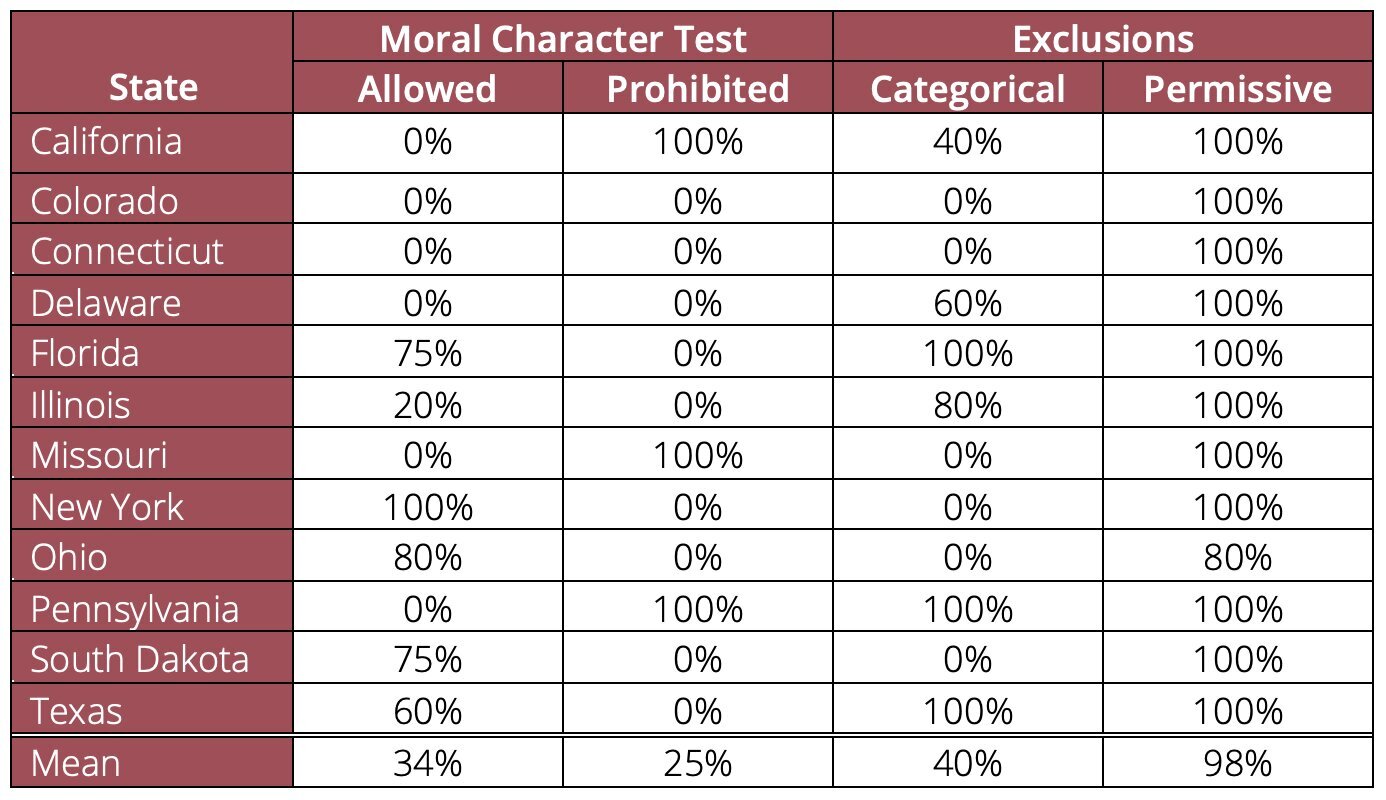

We studied five entry-level allied health professions (dental hygienist, occupational therapy assistant, physical therapy assistant, respiratory therapist, and radiologic technologist) in twelve representative states (California, Colorado, Connecticut, Delaware, Florida, Illinois, Missouri, New York, Ohio, Pennsylvania, South Dakota, and Texas), covering 24% of the states and 50% of the U.S. population to determine the regulatory framework for obtaining a license to practice an allied health profession (abbreviated AHP). AHP is an umbrella term used to describe the many jobs that help support the delivery of health care. These professions are attractive, because a college degree is not required, salaries are high and job opportunities are plentiful.

All twelve states license four of the five professions we studied, and a majority of those states (8 of 12) license the fifth (radiologic technologist). Historically, most states relied on a “good moral character” test to evaluate licensing applicants, but our data shows that many states have moved away from relying on these tests. Indeed, 3 of the 12 states explicitly prohibit their licensing boards from evaluating “moral character” when reviewing licensing applicants; however, six states still have this requirement for at least some of the licensed allied health professions. Moral character is an open-ended standard; one licensing board might view too many traffic tickets or an arrest for under-age drinking as a sufficient basis for denying licensure, while another licensing board might only consider more serious criminal offenses.

What do states use instead of a moral character test? The most common approach is to have a list of offenses that provide a categorical or permissive basis for exclusion. “Categorical exclusions” are criminal offenses that automatically preclude the issuance of a license, while “permissive exclusions” are left to the discretion of the state licensing authority. Permissive exclusions are the favored approach; six of the twelve states have no categorical exclusions. We also find about half the states limit the scope of discretionary exclusions to convictions that are substantially related to the scope of services that will be provided by the licensed profession. For example, if the AHP handles prescription drugs, a conviction for drug possession would be “substantially related,” but otherwise not relevant.

State-Level Licensing of Five AHPs

More Can be Done

Our findings show that many states have moved away from open-ended “good moral character” tests in favor of a list of offenses that provide a basis for either categorical or discretionary exclusion. This approach can simultaneously give state licensing boards more discretion (by creating a list of permissive exclusionary offenses), and less discretion in other domains (by requiring past criminal offenses to be substantially related to the scope of services provided by the AHP).

More can be done to inform licensing applicants with a criminal record as to how state boards will handle their particular case. Little has been done to make such information more accessible and salient to applicants and those considering undergoing the necessary vocational training. It is one thing to know that some crimes constitute a permissive basis for exclusion, and entirely another to know that the state board ultimately awards a license to 5% (or 95%) of applicants with those crimes on their record.

The failure to make public the “common law” of how state licensing boards handle applicants with criminal records is an under-appreciated factor deterring such individuals (who are disproportionately likely to be from historically marginalized groups) from even considering obtaining the training to enter into these fields. Fixing these impediments should reduce recidivism by improving the employment prospects of ex-offenders, and can reduce any disparate impact of the regulatory regime that all states use for deciding who can become a licensed allied health professional.

Read more in Jing Liu and David A. Hyman, “Criminal Records and Licensure in Five Allied Health Professions: Is There Evidence of a Disparate Impact on Historically Marginalized Groups?” Journal of Health Politics, Policy and Law (2022).

Research for this brief and the underlying journal article was supported by the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation.