The Great Recession and America's Underemployment Crisis

Connect with the author

In 2007 the U.S. economy entered the Great Recession, a steep contraction stretching from December of that year to June 2009. This downturn now stands as the worst for the United States since the Great Depression of the 1930s. Americans lost a tremendous amount of wealth, especially in home equity, and the labor market turned markedly worse for many workers.

Official unemployment statistics have gotten steadily better in recent years, but they do not capture the full picture of labor market hardships Americans are facing, especially in the aftermath of a crisis like the Great Recession. The broader concept of underemployment includes all situations in which workers are not employed full-time – at the number of hours they wish to work – in jobs that pay above-poverty-level wages. A good measure of underemployment, the Labor Utilization Framework, encompasses four sets of affected workers:

- Discouraged workers: Refers to individuals who would like to be employed but are currently not working and have not looked for work in the past four weeks because they are discouraged about their job prospects. The official unemployment rate reported in the media each month does not include these would-be but discouraged workers.

- Unemployed workers: Consistent with the official definition, this includes unemployed people who have looked for work during the previous four weeks or are currently laid off but expect to be called back to their jobs.

- Involuntary part-timers with low hours: This category is consistent with the official definition of those who are working less than 35 hours per week only because they cannot find full-time employment.

- Low-income working poor: Includes workers employed 35 or more hours per week whose average weekly earnings in the previous year were less than 125% of the poverty threshold.

All other current or would-be workers are defined as adequately employed, while those who are not employed and indicate no desire to be so are defined as not in the labor force.

Trends in Underemployment from 2002 to 2012

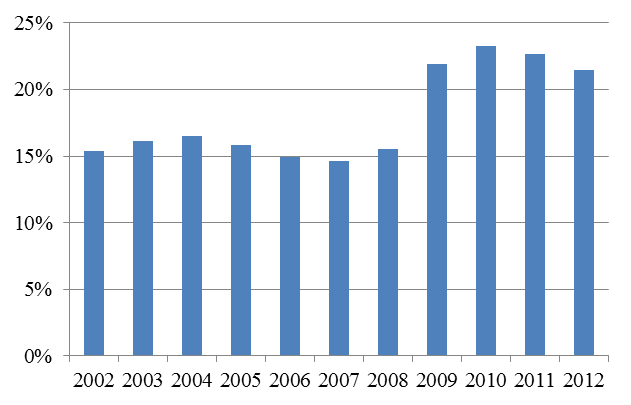

Data drawn from the nation’s most comprehensive annual labor force study, the Current Population Survey, can be used to trace the employment circumstances of Americans aged 18 to 64, in the prime of their working years. The following figure shows the total percentages of workers who were underemployed from 2002 to 2012. Bearing in mind that the effects of economic downturns happen with a bit of delay, the devastating impact of the Great Recession could not be more evident. After averaging 15.5 percent from 2002 to 2008, underemployment increased to an average of 22.4 percent from 2009 to 2012. That is a staggering jump of almost seven percentage points. In the wake of the Great Recession, more than one in five prime-aged U.S. workers found themselves in the ranks of the underemployed.

Percent of Labor Force Underemployed, 2002-2012

Our more detailed analyses show that, in comparison to the period of 2002 to 2008, the post-recession years from 2009 to 2012 saw significant increases in discouraged workers and involuntary part-timers, in addition to the publicly visible jump from 5.4% to 9.1% in the percent of officially unemployed. The only type of underemployment that bucked this trend was underemployment due to low income, which remained statistically unchanged between the two periods (averaging 6.2% across all 11 years). This is a source of concern because it indicates that the rise in general underemployment following the Great Recession was driven by growth in the more severe forms of employment hardship.

What Persistent High Underemployment Means

Our findings underline clear policy challenges. Most obviously, official unemployment statistics underestimate the depth and persistence of labor market hardships affecting big segments of working America. Being out of work and actively looking for a new job is only one part of the problem. In fact, an especially troubling sign during and after the Great Recession has been the upwards bump in discouraged workers who have given up on job searches entirely. We do not yet know whether these once-willing workers will remain discouraged or resume job searches as the economy gradually recovers – but there will be important social and economic consequences either way. Indeed, it is important for policymakers and the public to grasp that underemployment persists well beyond the official end of a downturn. The Great Recession supposedly ended in June 2009, but underemployment grew for years thereafter. The first signs of recovery do not mean decreased hardship for tens of millions of working people. Safety net protections like unemployment insurance and food stamps continue to be much needed well after a downturn – especially one as deep and slow to reverse as the Great Recession.